1

The afternoon they were supposed to bury the sinister Don Pedro Lobo, one of the most unforgettable stories in the town’s history took place. It caught me completely by surprise, because up until that day, I thought there were only a few people in town who actually appreciated the now-deceased.

I was eleven then, and El Tablón was still a decent place—where people came not just to eat, but to chat, hold small gatherings, and trade the latest gossip from town and the vicinities. What drew everyone there was simply having a good time.

My dad used to take me there on Sunday afternoons. The warmth, the amber glow of the lights, the music, the hum of conversation all wrapped in the scent of freshly cooked food, stepping inside always felt like crossing into another world. And the bread pudding, made from leftover bread, the best I’ve ever had.

There was one person in particular who frequented the place with enthusiasm—a young man everyone called Pepe Ice. They said he’d earned the nickname for keeping his cool in situations that would’ve rattled anyone else. At least, that’s what his closest friends claimed.

That afternoon, a crowd had gathered there to have a drink and talk about the funeral. Pepe wore black boots, gray trousers, a beautiful blue velvet cape, and a black shirt with a silver cross hanging from his neck—in short, one of his finest outfits.

“May God forgive me for this toast!” he said, raising his glass of rum. “To a few years of peace and quiet, now that old Lobo has gone to the other side. Cheers!”

Pepe downed his drink in one gulp, but when he set the glass back on the counter, only a few joined him. My father was one of those who didn’t raise his glass, even though he had a drink sitting right there on our table.

“Come on, people! A few little acts of charity won’t redeem a whole lifetime of wickedness from old Lobo,” Pepe went on. Again, only a few answered with a half-hearted “yeah,” but the silence that followed was quite uncomfortable.

“I’m telling you, he must be in hell by now. He wasn’t just greedy—he was probably up to something downright evil.” A few murmurs rippled through the crowd.

At that moment, I remembered a rumor my classmates used to whisper at school—about a gardener who once worked at Don Pedro Lobo’s mansion. He claimed to have seen a secret room painted entirely red, filled with strange altars and odd-looking candelabras.

“Of course, go ahead and blame everything on the dead,” answered a deep voice.

Everyone turned to look toward a dark corner of the room. The voice had come from an older man dressed in black, with gray hair and a scruffy beard.

“There’s no one completely evil, nor anyone completely good,” the old man added, then took a sip of his drink.

The murmurs started almost immediately.

Pepe’s gaze snapped toward the man.

“He never did a good deed that wasn’t meant to benefit himself. So tell me, Don Peregrino—what act of kindness do you remember him for?” Pepe threw his cape back, revealing the shining cross on his chest.

“I’m only saying that nothing is ever what it seems. Just as Don Pedro Lobo—may he rest in peace—wasn’t entirely evil, the good priest isn’t entirely good either.”

The murmurs turned into a scandalized uproar, though not everyone seemed to disagree.

“That’s a serious accusation!” Pepe shot back. “How dare you defend a scoundrel and insult a man of faith?”

As for me, it wasn’t the first time I’d heard about Don Peregrino’s boldness. He was a stern man who rarely attended mass, but he was always lending a hand where it was needed.

“Faith has nothing to do with it,” Don Peregrino replied. “People are who they are—just like this diner. It’s not exactly a bar, but it’s not a family restaurant either. It simply is what it is.”

This time, a few laughs followed.

“A thief, that’s what he was. Hoarding wealth while so many went hungry—that’s all he ever did.” Pepe said.

Right then, he extended his glass for the bartender to refill it, never taking his eyes off Don Peregrino.

“Well, believe it or not, more people had something to eat thanks to Pedro Lobo than by going to church.”

At that moment, I turned to my dad. Everything I was hearing felt wildly bold to me; he, however, seemed either upset or sad, I couldn’t tell which.

“Apologize! Right now!” Pepe said, after draining the entire glass and slamming it down hard on the counter.

Scratching his head, Don Peregrino looked around and then continued.

“Don Pedro was ruthless in business, that is true.” Don Peregrino said, “but it’s also true that many of the good things he did, he did in secret—acts that went far beyond simple charity.” And as he said this, he looked around the room again.

“I challenge at least half the people here to deny what I’ve just said.”

A few voices grumbled in protest, but when I looked around, most people were shifting in their seats, trying to look anywhere else.

“You see, boy?” said Don Peregrino. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” And with calm, he took a sip from his glass.

Pepe’s face turned red with fury. He narrowed his eyes and stepped forward.

“Old Lobo stole from my family—he betrayed my father when they were business partners and left us in ruin. How can there be any goodness in a man like that? You’re the one who doesn’t know what he’s saying!”

Don Peregrino took another sip of his drink, unfazed. The crowd waited; tension was in the air.

“He most likely did steal from you,” the old man said. “But on the other hand, you were just a child back then, and old Pedro isn’t here to confirm your father’s version of the story—may he rest in peace.”

Pepe moved closer to the tables, wanting to be nearer to his “opponent.”

“Don’t talk about my father!”

“I haven’t. You did.”

“Old Lobo was pure evil! Do you know that with the money he stole from us, he had that gold cross made, the one he used to wear over his chest? A gold cross... for a man who had a pact with the devil himself!”

Everyone in the room was alarmed, I was scared, but at the same time, thrilled. Not even my parents had ever argued so fiercely.

“I’m just saying that nothing is ever quite as they say,” Don Peregrino said, raising both hands as if trying to free himself from blame.

Then he added, “And you, Pepe Ice, I don’t think you’re as brave as they say. Insulting a dead man who can’t defend himself, someone you barely even knew? I’d say that’s quite a coward right there.”

Pepe snorted with rage.

“Oh, really? You hide behind words, knowing we can’t settle this like real men because you’re just a feeble old man. Who’s the coward?”

Laughter erupted—but it died immediately when Don Peregrino rose from his chair. My father remained seated, watching the scene intently. I was itching to ask him who was right, but just as I opened my mouth, he raised one hand to signal me to keep listening, while placing his other gently on my shoulder.

“There’s nothing you and I need to settle,” said Don Peregrino, trying to calm things down. “I never stole from your family, and Pedro Lobo wasn’t the monster you claim he was.”

Don Peregrino finished the last sip of his drink and set the glass on the table.

“But know this, I take back nothing I’ve said.”

Then he reached for his jacket—also black—and began putting it on.

“However,” Don Peregrino went on, “since you weren’t brave enough to say any of this to Don Pedro while he was alive, why don’t you pay him a visit at the cemetery tonight and tell him everything you’ve told us here? Now that he’s dead, maybe he won’t scare you as much.”

The place erupted into an uproar. It took Don Peregrino a while to make himself heard again—but eventually, he managed to continue.

“I know Simón well, he might be an excellent gravedigger, but he’s lazy. I’d bet anything that Don Pedro’s coffin is still there, covered with just a few inches of dirt on, and will stay that way until the early morning.”

Everyone turned to Pepe, who stood silent and stone-faced for a long moment.

Don Peregrino stepped away from his table, bid farewell to the crowd, and as he passed by Pepe, he stopped. He put on his black hat and whispered something in Pepe’s ear. The young man did nothing, just remained there, still and deep in thought.

2

The subject cooled off for the rest of the afternoon at El Tablón, and we left a little before dinner. On the way home, I decided to break the ice about what had happened.

“Quite a character, that Don Peregrino, huh?” I said to my father as we walked along the nearly empty sidewalk.

“Quite a character?”

“Yeah, how could he say Don Pedro Lobo was a good man? If you only knew what they say at school, not just about the red room, but also…”

“Son,” he said flatly.

“Yeah?”

That’s when I realized he had stopped walking and was a few steps behind me.

“You don’t know what you’re saying,” he said. “But, I don’t blame you. Your mother and I haven’t told you anything.”

“About what?”

“Come on, walk with me. We’re going to Jonás’s store.”

Once there, my father picked out a new rope, and while we were at the counter paying for it, he pointed toward a small altar at the back of the store. When I looked, I could make out a tiny black-and-white photograph with two lit candles on either side.

“See that picture over there?” My father whispered.

“Yeah, but I can’t really tell who it is. A saint?”

“No, son. Not a saint,” he said just as Jonás approached.

“Is that all?” the shopkeeper asked with a friendly smile.

“That’s all.” My father replied, handing a few coins.

“Hey!” Jonás added as he counted the change, “Did you hear what happened at El Tablón this afternoon?”

“We were there,” my father said, placing a hand on my shoulder.

“So, do you think Pepe’s actually going to do it?” Jonás asked, a trace of concern in his voice.

My father only nodded—like he was just then deciding to believe it himself.

“Hey, José” Jonás added. “We all knew Don Pedro, but profaning? That’s too much. I’d do something about it myself, but…”

“It’s too much,” my father said, putting the rope away.

“We could do something, you know, if we talk to the others. All the old friends.” Jonás glanced at me sideways as he spoke.

“There’s no need,” my father said. “I’ll stand watch tonight.”

Jonás looked him in the eye for a few seconds.

“Be careful. Pepe’s crazy.”

“Don’t worry.”

I had no idea what they were talking about.

“Come on.” My father said, placing his hand on my shoulder.

We stepped outside, and the stars had vanished behind thick, purple clouds. Once home, my father went straight to the kitchen. He pulled out the small pot he used to brew morning coffee and set it on the stove with a bit of water.

“Son, come here.”

I obeyed. Once I was seated, I watched him take the coffee tin down from the cupboard.

“Sit down, please.”

“What’s going on, Pa?” I asked, wondering what had gotten into him. He sat down and placed two empty cups on the table.

“And the second cup?”

“It’s for you,” he said, dead serious.

“But, Pa…”

“Son, you need to know that when your mom and I got married, we were just two young people with more hunger to live than a real plan to keep a household going.”

“Yeah?”

“Don Pedro gave us both a job—right when we were about to get kicked out of the tiny room we rented near the central plaza.”

“Oh, your first house?” I said, remembering I’d heard that story once before.

“Yes. And thanks to the time we worked for him, people got to know us, and we built up our trade. So much so that, three years ago, when Don Pedro fell ill and shut down the business, your mother and I already had a good reputation, and we haven’t lacked work since.”

The water pot began to boil, and my father got up to add the coffee. The small dining room filled with its aroma.

“So… does that mean Don Pedro Lobo was a good man? But what about the rumor of the red room? Was it a lie?”

While stirring the pot’s contents with a spoon, my father repeated the words Don Peregrino had said earlier at El Tablón.

“No one is entirely good, nor entirely bad.”

“Then? What’s Pepe Ice going to do? That thing about professing...?”

“Profaning,” he corrected me.

“That, what is it?”

“It means opening a grave, or a coffin.”

The hairs on the back of my neck stood up, and I crossed myself.

“Seriously?”

My father nodded.

“But… why would he do something like that?”

He looked at me again and said nothing, just let out a sigh.

“Pepe’s just like his old man, never knew when to leave things alone. And Don Peregrino, well, he always knew how to poke the bull right in the horns.”

He stood up and brought the pot and a strainer to the table.

“And why do I have to drink coffee?” I asked.

“Because tonight, you and I are going to the cemetery, to stop Pepe from doing something he shouldn’t,” he said as he began pouring the coffee.

At first, I thought he was joking, but then I saw him pull out his bag from under the kitchen table.

“Dad, I don’t think Mom would like the idea of us going to the cemetery at night.” My mother wasn’t home those days, she was away on a church retreat.

“You’re right, your mother wouldn’t like it. But she’d be even more upset if I did nothing,” he said, standing up again to grab the sugar bowl and place it next to my cup.

“Come on now, drink up, we’re leaving as soon as you’re done.”

3

The cemetery’s main gate, the one we used to enter through on the Day of the Dead. was locked. I felt a wave of relief that would not last long.

“Come on, follow me.” My father said, and we walked along the fence until we reached a spot where the foliage from some trees blocked the streetlights. My father then showed me a gap where the bars were bent. He tossed his cloth bag over the fence, and then we squeezed through the narrow space, as the smell of rotting leaves and pees flooded my nose.

My heart was pounding. I’d heard plenty of stories about being in a cemetery at night, and none of them ended well.

Once inside, we gathered our things and I followed my father, who moved quickly. We dodged the graves in our path until we reached a deeper part of the cemetery, where the stench wasn’t as strong and the trees gave off that typical nighttime scent they always have.

I had the strange feeling that I could hear footsteps other than our own, but my father made a face at me, signaling to keep quiet and move along.

“But, Dad.” I whispered, “I think there’s someone else out there.”

“Shhh, quiet.” He said, tugging on my coat so I’d keep up with him.

The cold was beginning to seep into my bones, but I didn’t want to complain, my father wouldn’t listen to reason in moments like this. We reached a lower fence, the one that separated the town’s graves from the larger ones, where the important people were buried. We climbed over it easily, and my father pointed toward a spot where there was a light.

For a moment, I thought I heard more noises coming from some bushes behind us, but before I could say anything, my father grabbed me by the shoulders and we crouched behind a grave. Then, he pointed out in the direction of the light.

There, a man wearing a cape and a wide-brimmed hat was digging fast, as if he didn’t care to go unnoticed. The lantern sat to the side, resting on top of the mound of dirt.

“It’s him.” my father whispered. “Stay where you are.” Then he began to rise, ready to step out from our hiding spot.

I kept my eyes on Pepe’s movements and saw that, at that moment, he heard something too. Maybe us, or perhaps the other noises I’d picked up earlier. He drew a machete and drove it into the ground. My father froze. Until then, we hadn’t considered that Pepe might become hostile. We hadn’t brought any kind of weapon or anything to defend ourselves, only a rope and some blankets for the cold.

Pepe picked up the lantern and, after looking around, pulled a hammer from his belt. He placed the lantern back on the ground and started removing the nails. My father hesitated—it was clear he wasn’t sure what to do. I could tell. There were moments when it seemed like he was about to leap out and throw himself at the grave robber, but then he held back. I couldn’t help but think that maybe it was my presence that kept him from doing something reckless that night.

Then, Pepe tossed the hammer aside and began to lift the lid. My father looked at me again and made a second attempt to step out. He was halfway there when a light blinded us. My heart skipped a beat, but I soon realized it was just Pepe’s lamp. My father managed to hide behind another tombstone, this one a little closer to the scene.

Pepe held the lamp in one hand and a sheet of paper in the other. He began to read it aloud, his voice something between a shout and a whisper that refused to be either.

“He stole from the poor… betrayed his business partners… turned on his friends… drank himself senseless…”

Shivering, listening to that long list of sins while behind a tomb, I couldn’t help but imagine the dead rising up to dance, stirred by all that racket. But then I thought about all the honorable, kind people buried there too. What would they do? Or were they already in heaven?

Only a few minutes passed, but to me, they felt like forever. I didn’t know if my father would need my help.

“…And he made a pact with the devil!” Pepe finished the sentence with a special kind of solemnity. He glanced around, as if expecting someone to respond. He clearly knew he wasn’t alone.

“GOD IS MY WITNESS. THAT EVERYTHING I’VE SAID IS TRUE!”

He paused. The lamplight lit up his face; with defiant eyes, he glanced around once more. Then he folded the paper and placed it inside the coffin.

“You’ll take your sins to the other world!” He declared, reaching for the wooden lid to nail it back down, but then, he froze, staring into the coffin.

At first, I thought Pepe Ice had finally gotten scared. But then, without hesitation, he reached down into the coffin as if searching for something. A few seconds later, he yanked his arm back violently, pulling something out and raising it into the air. He brought the lamp closer to the object, and from where I hid, I saw it catch the light—it was something on a chain.

And then I remembered the gold cross Pepe himself had mentioned earlier that afternoon at El Tablón.

I still don’t know if what happened next was just one of those unlikely coincidences or if there truly are other forces out there, lurking and waiting for us to do something that awakens their macabre curiosity.

Pepe tucked away the object he had taken from the dead man, and just then, a cold breeze struck us. A second later, the sky lit up with the flash of lightning. A few seconds after that, the heavens roared with a powerful clap of thunder.

Despite being warned by the lightning, the thunder shook me so violently I jumped, even though I was sitting down. When I landed, a sharp pain from a pebble stabbed me right in the butt. I turned around and hid behind the tomb again, pressing my back against it, trying to catch my breath and rub my butt at the same time. For some reason, I didn’t dare look back at the scene.

It wasn’t until I heard the sound of the hammer again that I dared to peek. Pepe had started nailing the lid of the coffin back in place, but by then, the wind had picked up and the first drops of rain were beginning to fall on us.

My father was still hiding behind the other tomb, though he looked unsure. It took me a moment to realize he was trying to get my attention from his hiding spot. He kept pointing toward the gravedigger’s cabin. Just the thought of going alone filled me with dread. I had seen old Simón once before, and I remembered well his appearance wasn’t much different from the very corpses he buried.

Soon after, the rain began to pour harder. I peeked again and saw Pepe swing his cloak aside and accidentally stuck his lamp, which fell into a muddy puddle and went out. He tried to retrieve it, but it was too late, there was no way to light it again in all that water and mud. He returned to the coffin to keep nailing the lid shut.

Then I saw my father with the rope stretched out, and at the far end, Pepe’s machete was caught, like he had roped a bull. As my father began dragging it away, the machete clanged against a tombstone, making a noise that immediately caught Pepe’s attention.

In an instant, Pepe looked toward the tomb where my father was hiding. Despite the rain and the darkness, the rope stood out clearly on the wet ground. Then he swept aside his cloak, and I saw him pull a revolver from behind his belt. But as he jumped down from the muddy mound beside the coffin, it looked like he was pulled back by something, he slipped and fell hard on his back. I thought I saw the revolver fly out of his hand and vanish into the darkness.

My father ran toward me, the machete wrapped in a blanket and pulled me by the coat to follow him. We heard Pepe shout: “You bastard!” Just as more lightning lit up the sky, helping us make our escape, but we weren’t heading for the exit.

Between the tombs and the trees, I caught sight of the lights from the gravedigger’s cabin. The rain was pouring in torrents. We reached Simón’s porch completely soaked, just as the old man stood in his doorway, struggling to open an umbrella with no success. Under any other circumstance, the scene might’ve struck me as funny: This huge, pale man fumbling with a tiny umbrella that looked absurdly small in his hands.

My father tried to explain what was happening, while Simón looked as baffled by the idea of someone profaning a grave in his cemetery as he was by seeing the two of us there.

“There might be others. I imagine he brought witnesses.” My father said, just as another distant shout rang out.

“Let me go, you bastaaaard!”

I figured Pepe must’ve been struggling with someone, someone else who, like my father, wasn’t too pleased about the idea of someone desecrating the grave of a man they considered a benefactor.

I could see the distress on my father’s face. Without waiting for Simón to open his umbrella, he took off running and motioned for me to follow.

—Nooooo let meeeee gooooo! —another scream rang out as we made our way through puddles and tombstones.

I moved only because my father was leading the way. I could hardly believe I was running through a cemetery, at night, in the pouring rain, and toward someone screaming.

A third scream echoed before we reached the spot. This time it was:

—I’m sorry, I’m soooorrry, let me gooo!

I was still a few steps behind my father when I thought I saw a dark figure moving behind some tombs to my left, heading in the opposite direction. I froze for a moment, but another scream pushed me to keep going after him.

When I arrived, my father stood about ten steps from Don Pedro Lobo’s grave. His eyes were fixed on what lay before him: the open pit, and next to it, the wooden coffin, sealed, rocking violently from side to side. Behind the mound of dirt, Pepe Ice writhed on the ground, kicking and thrashing. His arms struggled to free himself from his cape, which seemed to be getting pulled into the coffin, as if it were being swallowed whole.

My father was stepping back, and I clung to him tightly. Despite the terror coursing through me, I couldn’t look away from the scene.

“What’s happening?” I kept asking him, but he stayed frozen, eyes fixed on poor Pepe, whose screams were now broken by gulps of muddy water spilling into his mouth.

Simón arrived just after us, soaked to the bone. He clearly hadn’t managed to open his umbrella. He stopped beside us and stared at the horror in front of us. Pepe could no longer form words; his cries had become a wheezing whimper that reminded me of a dog’s cough.

Simón looked at us briefly and handed my father a metal ring loaded with keys. Then, without a word, he turned and threw himself at the coffin.

We watched Simón wrestle with the heavy wooden coffin for a few seconds until, suddenly, he stopped. He examined the lid for a moment, then asked for the machete. My father seemed to snap out of a trance and handed it over. The gravedigger then slashed through Pepe’s cape, freeing him. Pepe rolled down the muddy slope like a ragdoll, landing in what now looked like a river of sludge. The coffin remained still beneath Simón’s weight.

“Is he a living dead?” my father asked.

Simón let out a laugh, which stroke me as horrible.

“Him?” he said, pointing at the coffin. “No, this one’s good and dead.”

Then, carefully getting to his feet, he pointed down the hill at poor Pepe, who was crawling aimlessly through the muck.

“And this one,” Simón added, “he’s just dead from fear.”

My father and the gravedigger carried Pepe, who was trembling and had gone stiff in a strange, unnatural way. By the time we reached the cabin, he was burning with fever and completely unable to speak. It took me a while to shake off the fear that the whole ordeal had left in me and to fully understand what had really happened. As Simón later explained, the poor fool had nailed his own cape to the coffin lid. Only God knows what must have gone through his mind when he felt himself being “grabbed by the dead.”

An ambulance was called to assist Pepe, since his condition was serious. However, before handing him over, Simón searched him, as my father had instructed.

“This drives both the living and the dead mad,” said the gravedigger in a solemn tone, holding up a gold chain with a finely carved golden crucifix hanging from it.

My father and Simón agreed not to report Pepe to the police. He seemed to have received more than enough punishment already.

The next day, Simón and his helpers gave Don Pedro Lobo the burial he deserved. The list of sins was removed from the coffin, and the golden cross was returned to the late man's lawyers, who came back to the village a few days later to handle matters related to his estate.

Pepe recovered, and though no one ever formally accused him of being a thief, he never set foot in El Tablón again; everyone knew what he had done. The tale of how he nailed his own cape to the lid of the dead man’s coffin was retold in vivid detail by Don Peregrino, who turned out to be one of the others sneaking through the cemetery that night, hoping to witness the bravery of Pepe Ice.

It became the most famous story ever told in the village, perhaps only surpassed by another, years later, when the same lawyers managed to open a sealed room in Don Pedro Lobo’s mansion… a room painted entirely red on the inside.

NOTE: The story you’ve just read is inspired by a tale my grandmother used to tell about a man she knew when she was young, who once entered a cemetery, opened a wooden coffin at night, just to prove his bravery, and accidentally nailed his own cape to the lid as he finished.

The character of Don Pedro Lobo is loosely based on a real, powerful family from El Salvador who, during the 19th and 20th centuries, owned extensive properties across the country. They were often surrounded by strange rumors, including whispers of a pact with the devil and the curious fact that they left behind no known heirs. Many of the old houses they once owned still stand today, some repurposed, and others said to be haunted.

One of my grandmother’s relatives who once worked for that family also shared the legend of the red room and swore it was true.

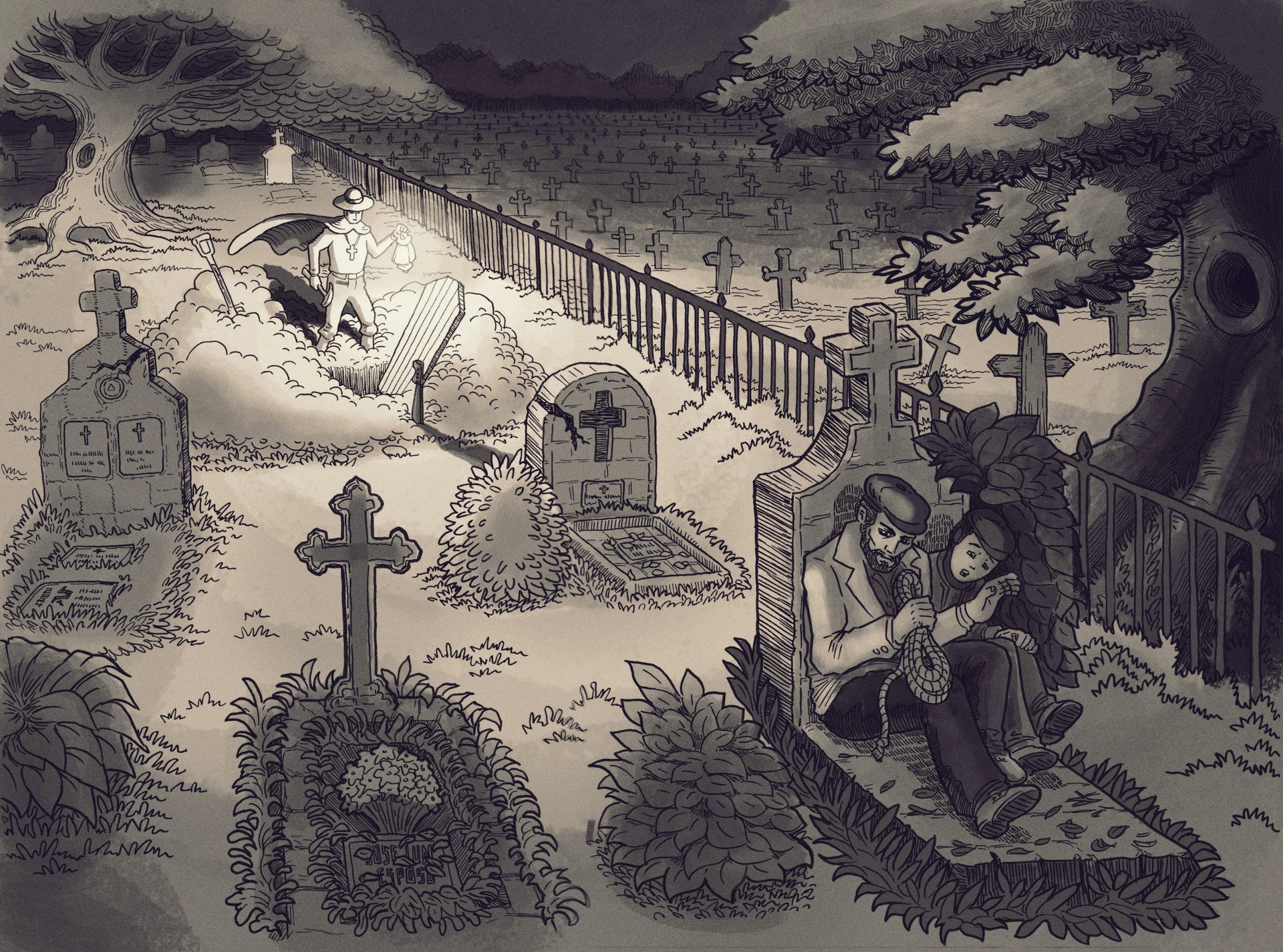

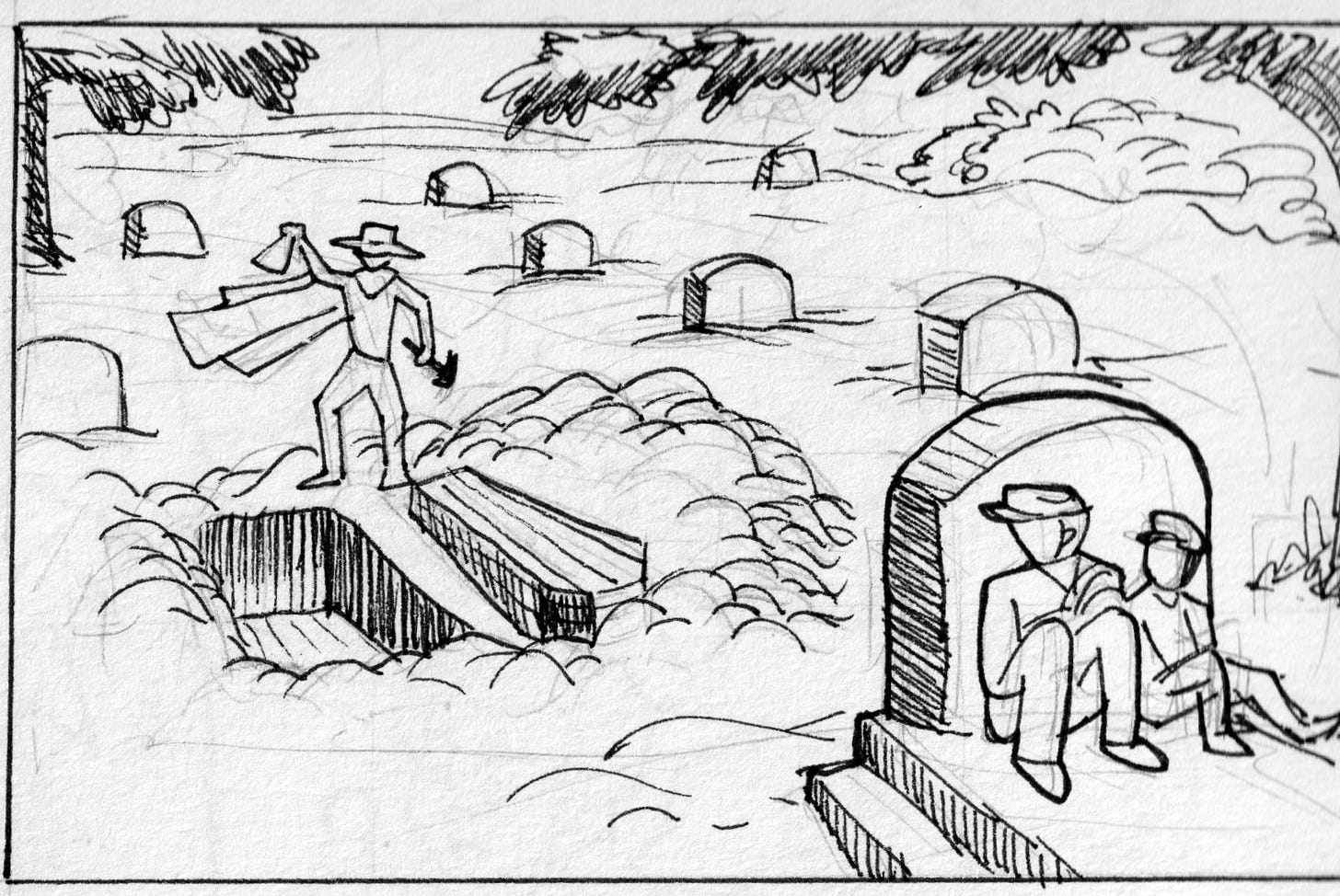

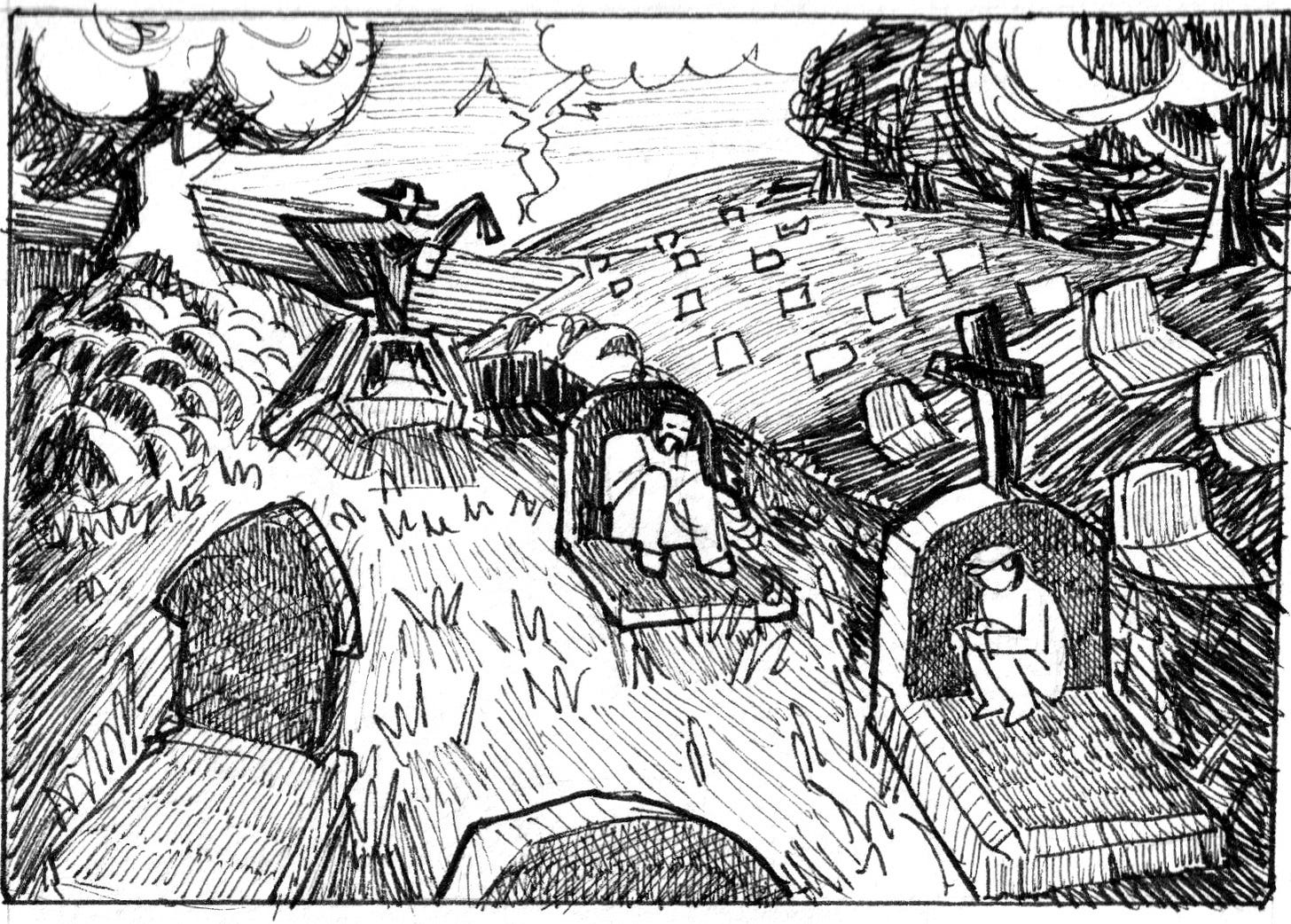

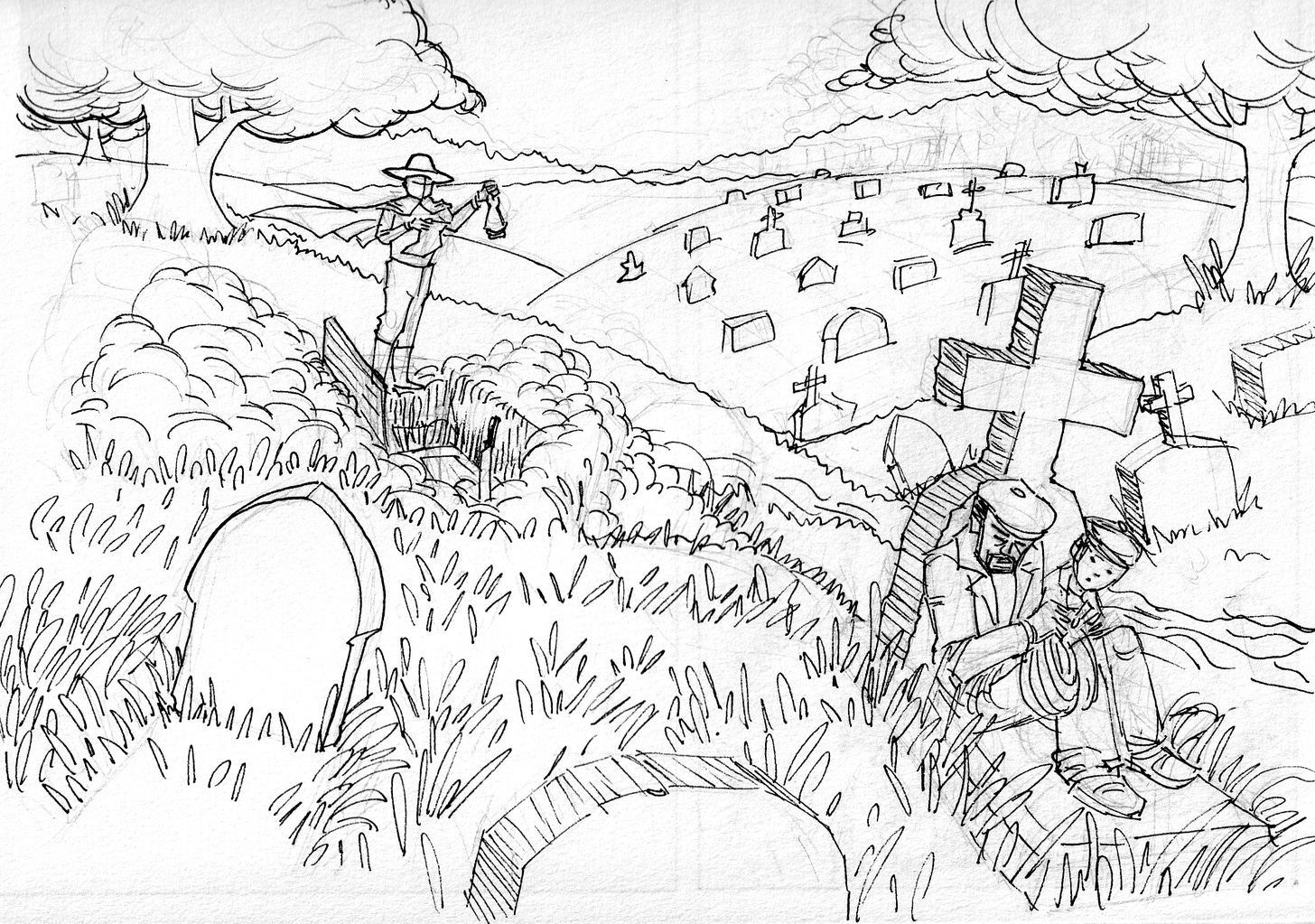

About the drawing

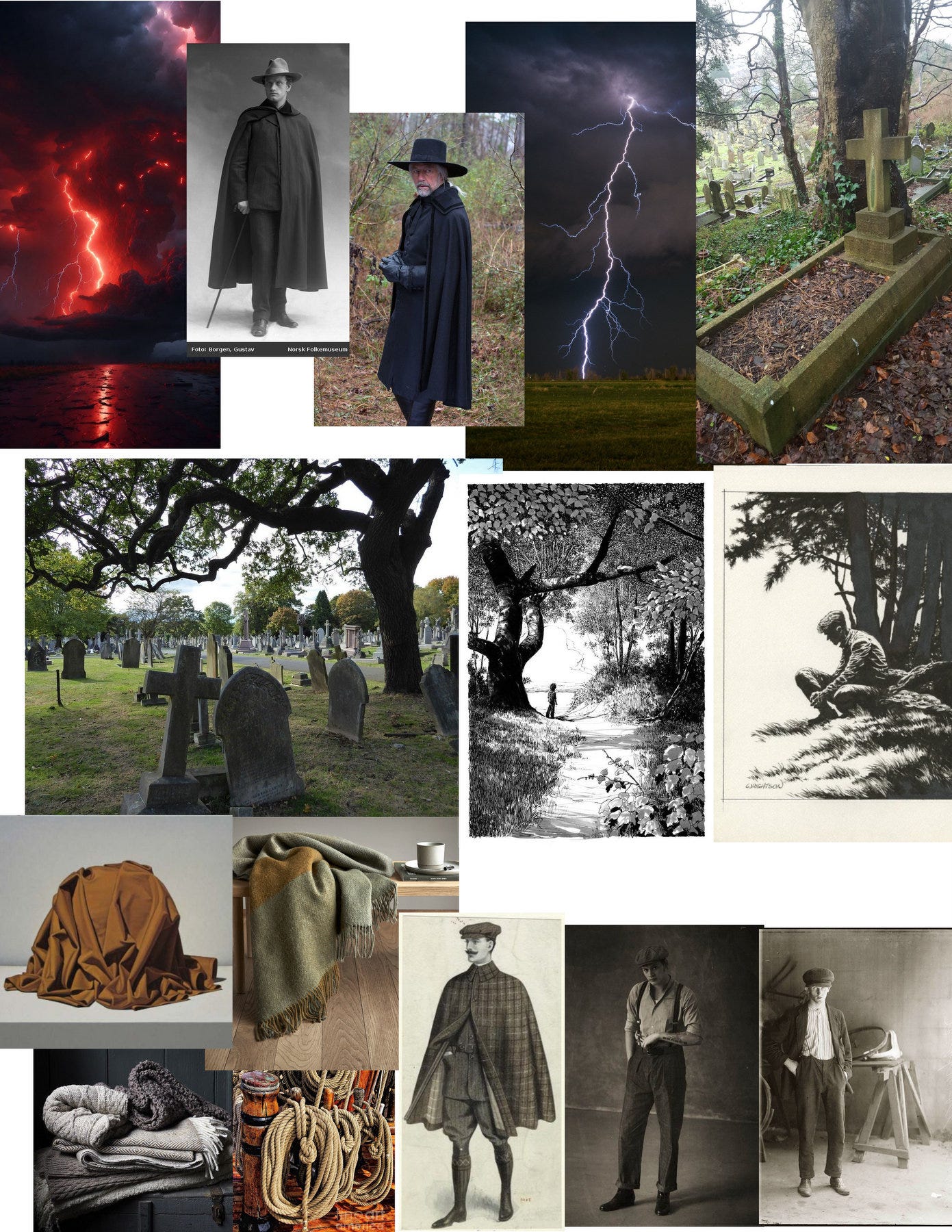

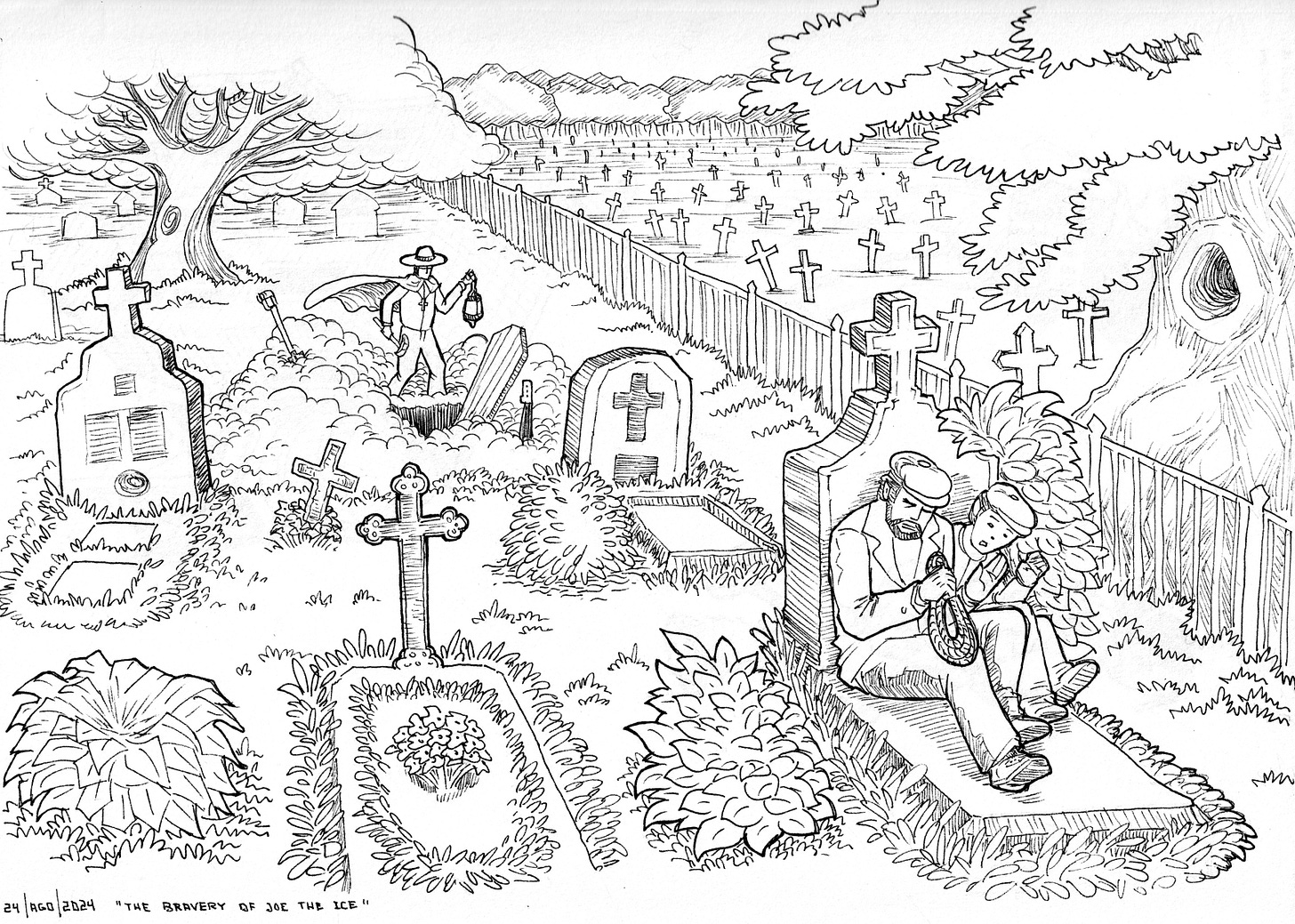

This is one of those drawings where my drawing method honors the importance of repetition. As you can see below, my first sketches, despite holding the same idea, differ in tone and atmosphere.

Until I managed to use a mood board to set up the right tone, one that was closer to how I saw the scene in my mind.

Moodboard:

Base sketch I ended up with:

Working sketch:

If you enjoyed this story and like my work, please consider liking, sharing, commenting, or buying me a coffee. I would greatly appreciate it. Until next time.