If someone were to ask me today, "What can you draw?" I might confidently respond, "Anything." But before you think I’m just being cocky, let me clarify. I don't claim to be an expert in every drawing style, nor do I believe that I won't face challenges with certain pieces. However, I possess something crucial in my artist’s toolkit when it comes to drawing: a method.

The result of a need

After the carefree phase of childhood, where I drew what I liked without worrying about the outcome, came a much more bitter stage in my artistic life. This period, probably between the ages of 18 and 30, was marked by repeated attempts to “achieve something” with my drawings, only to fail miserably and end up with nothing or a disappointing piece. Typically, these episodes were followed by dry spells lasting weeks or even months, during which I didn't sketch at all. This became a chronic issue, eventually leading to the embarrassing realization that I had spent an entire year without drawing. I can't recall exactly which year that was, but I still vividly remember the horror of realizing it.

It was during this difficult phase that I remember deciding to enter a drawing contest sponsored by the Japanese Consulate in El Salvador. I had a whole week to prepare, but I procrastinated until the night before the deadline. At 24, I was still quite naive about the importance of process, believing I could perfect a drawing on the first try.

That night, my "method" involved sitting at my desk with paper in front of me, visualizing the character in my mind, and attempting to translate it directly onto paper—almost by osmosis. Despite my efforts, nothing materialized as I felt it should; the image didn’t align with the cool, shifting vision in my head. Eventually, I gave up around 3 AM, completely burned out. The following day was tough, my face broke out in a rash, a clear reaction to the stress and lack of sleep.

One of the main reasons for this struggle was my failure to distinguish between being inspired and having a method. Inspiration is fleeting and, coupled with a dash of talent, might mislead an artist into thinking that a method isn’t necessary. In contrast, having a method empowers the artist to do the work under any circumstances, whether inspired or not.

Iterate

The first component of my method is something I resisted for many years: the necessity to redo my drawings. By this, I don’t mean merely erasing parts and trying again—which was my initial understanding of redoing a drawing. Rather, I mean completing a drawing fully and knowing I would need to do it again. Back then, the thought of taking a fresh canvas (or piece of paper) and repeating the entire process was not only intimidating but also felt incredibly tedious.

But what I’ve discovered is that the magic relies not on starting from scratch each time. Instead, it's about iterating over the previous sketch to improve it, which leads me to the second critical component of my method.

Scale

In 2015, I took a two-month course in Concept Art, and among the incredibly valuable lessons I learned was the importance of reusing my sketches, especially the smaller ones. I quickly realized that my poses, compositions, and use of negative space were significantly better when the sketch was small—a thumbnail, so to speak. If I had created a successful thumbnail, I didn't need to start over from scratch; my instructors taught me that I was "allowed" to trace my own sketches at a larger scale. After all, it was my own line art—there was no cheating involved, or perhaps, it was the ultimate cheat of them all.

When I combined these two key components, I developed what is now my drawing method.

The method

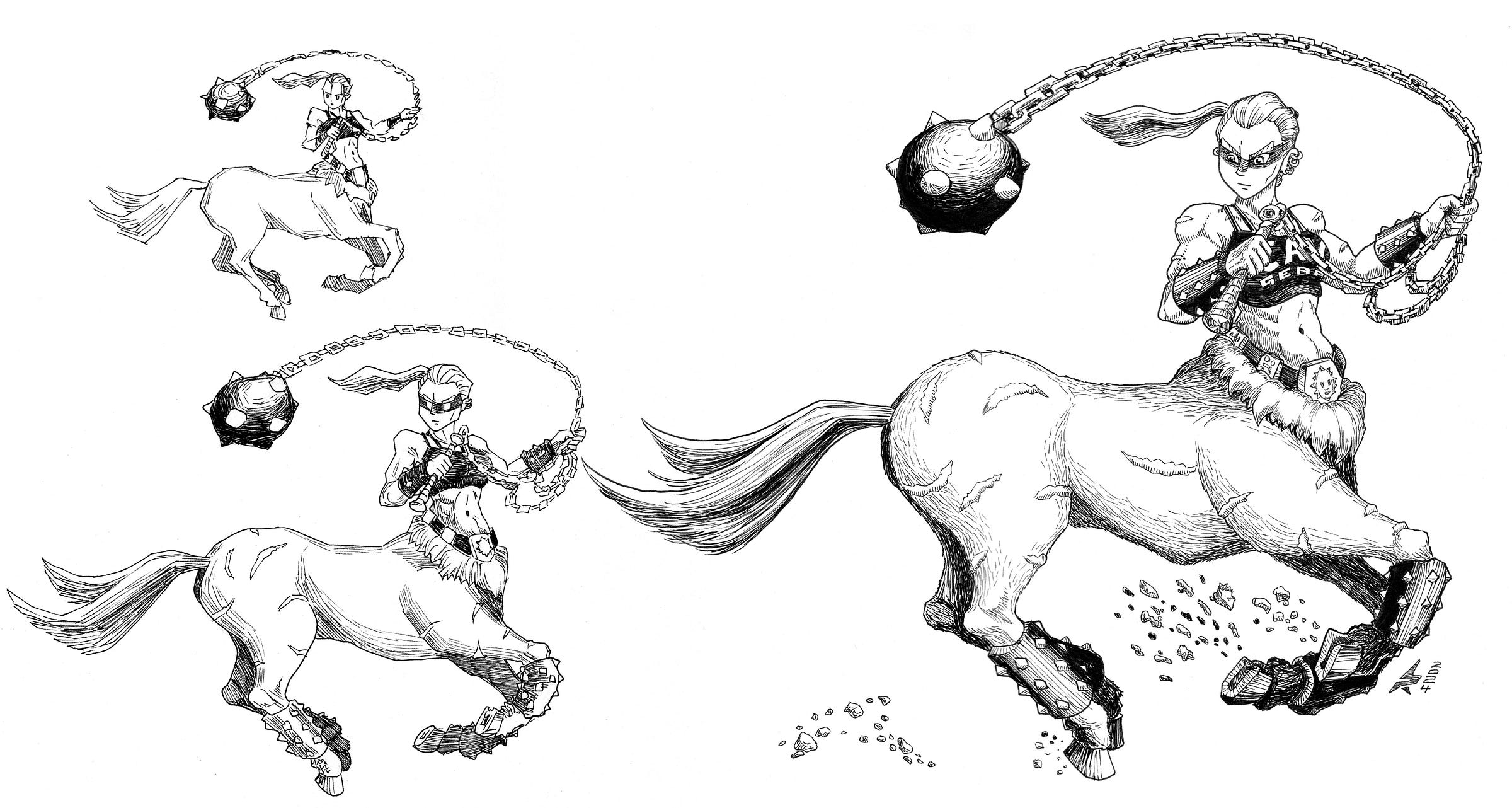

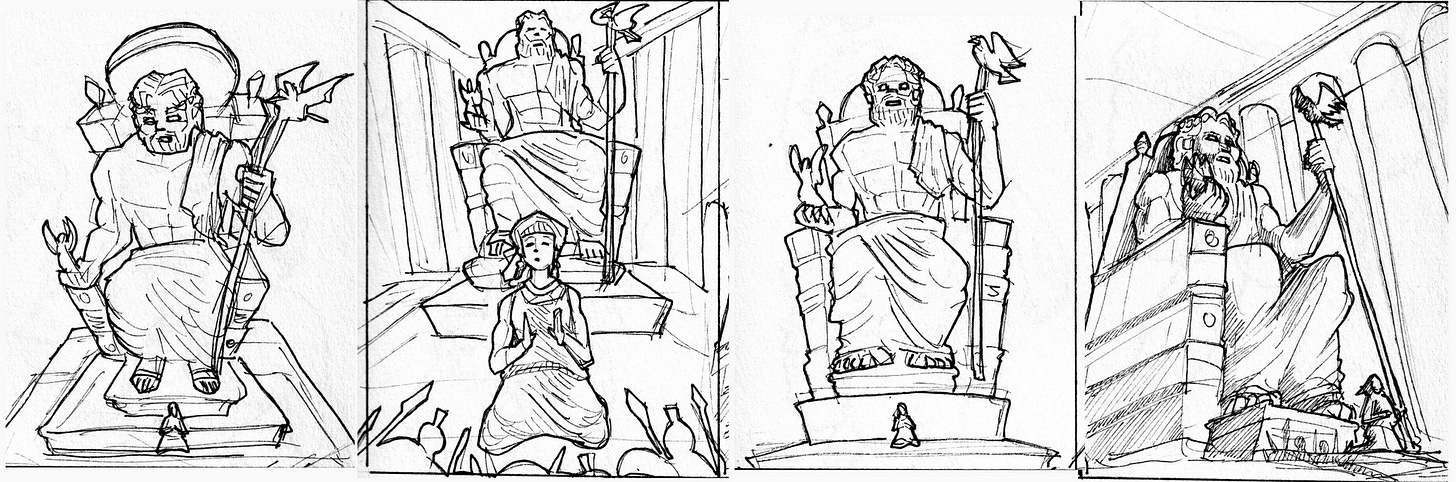

First, I explore the design or scene I want to draw with small sketches. I create as many thumbnails or exploratory sketches as needed until I find one that works—the one I like best. Since these are small, I can produce many in a relatively short time without too much effort.

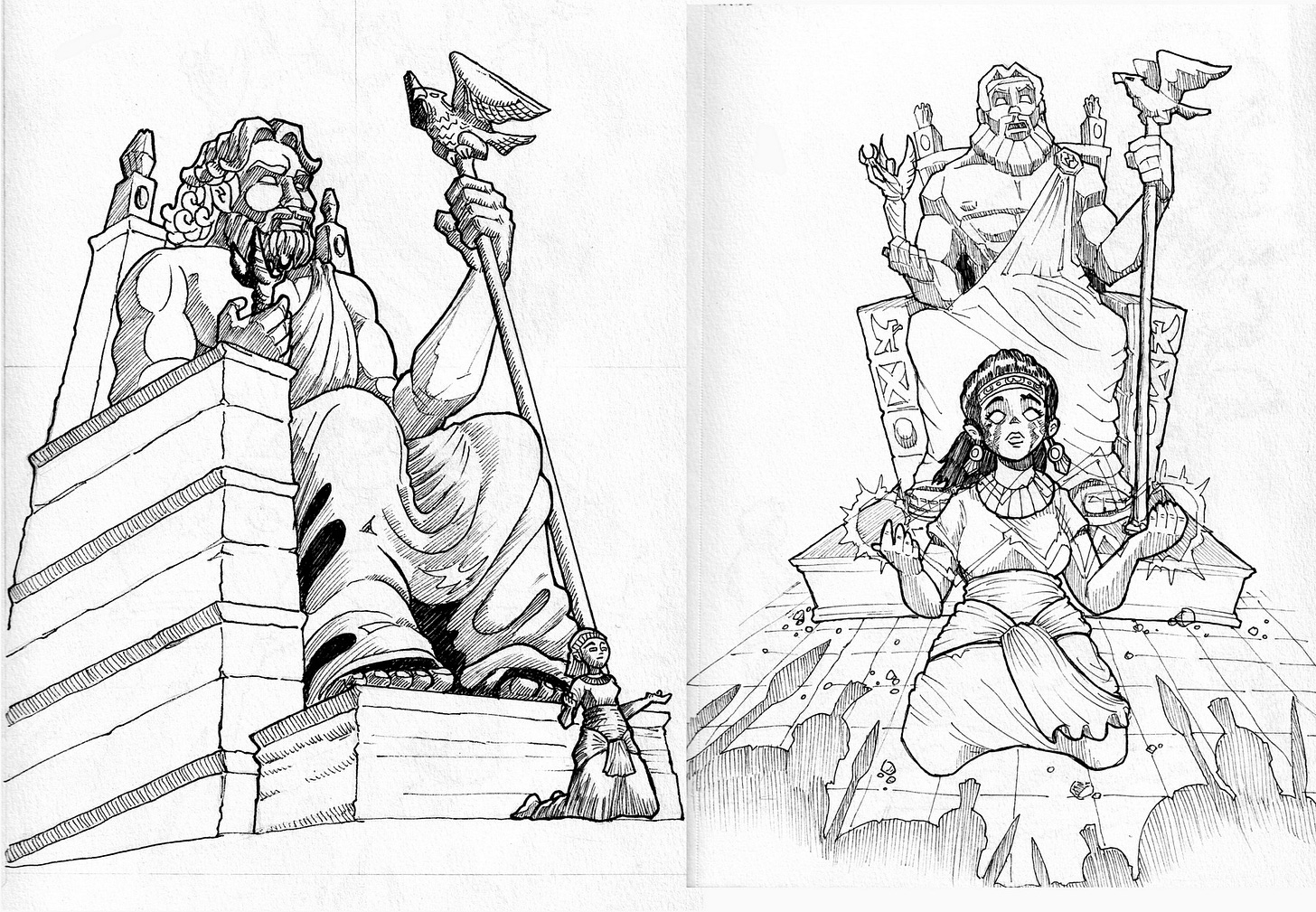

Secondly, once I’ve selected my favorite thumbnail, I scale it up and trace it into a working sketch. In this stage, I correct any proportional errors and add initial details, although my line art or crosshatching isn't fully polished yet. I also start to weave in concepts and themes. This stage may not involve just one working sketch; there could be several, though typically, in my experience, I iterate less on the working sketch.

Lastly, once I am satisfied with the working sketch, I scale it up again (only if necessary) and trace it onto the final piece. Believe it or not, this is sometimes the step I have to iterate the most. At this stage, all details, crosshatching, and line quality are expected to be final. If something isn’t working as it should in the polished final piece, then I need to redo it. The good news? I don’t have to start from scratch—all the shapes, designs, and compositions are already defined. This is where I can afford to be meticulous.

The key lies in iterating with purpose and scaling up thoughtfully. When I view my final piece, I can truly appreciate all the “invisible” effort behind it—and you know what? Other artists can see it, too.

What about inspiration?

Inspiration strikes every now and then, and when it does, it propels me forward within my own method—as the saying goes: “it finds me working.” I welcome inspiration when it arrives, but I no longer wait for it. Similarly, I avoid entangling myself in the false dilemma of drawing from references versus from imagination. I simply do what is necessary to achieve my goals. You'll find future posts on this topic, as it seems to be a common dilemma among artists today.

That could be considered a light version of my approach to drawing. I am eager to share more details about it in upcoming posts. Until then, happy drawing!